Thai Forest Tradition in the lineage of Ajahn Chah

Origins

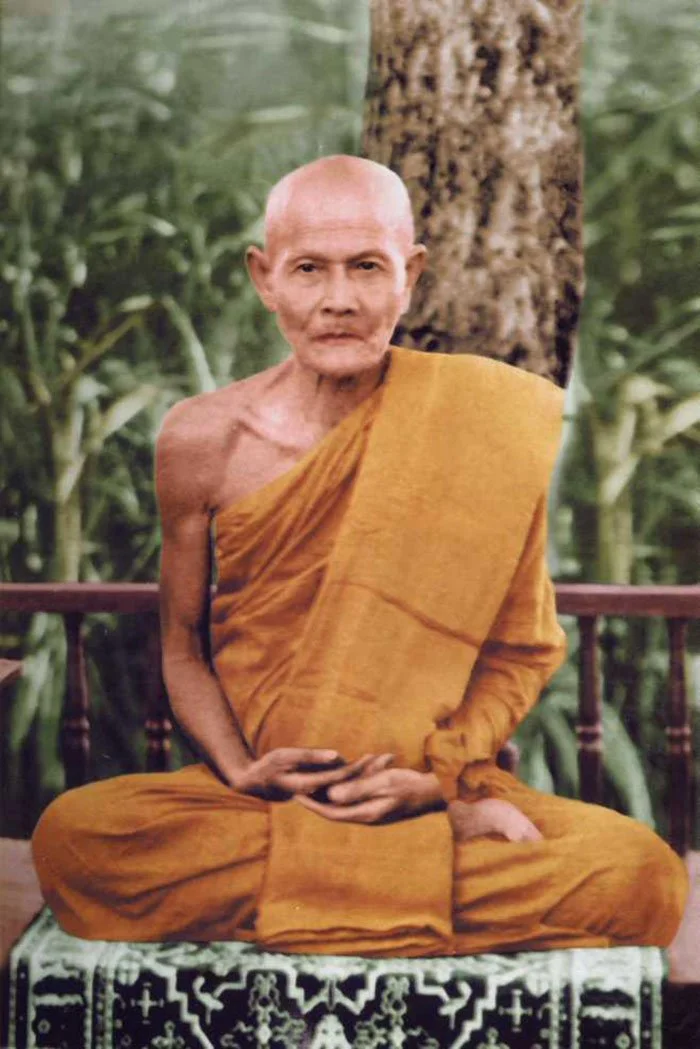

Ajahn Mun

The monastic lineage behind Dhammapala Monastery belongs to a branch of the two original Southern schools of Buddhism: the so called Sthavira and Mahasanghika, two groups who separated from each other already shortly after the second Buddhist council – which took place approximately 100 years after the passing away of the Buddha. Both groups represent the forerunners of all the southern schools of Buddhism, among them the Theravada tradition, which appeared on the scene under this name not until a hundred years later.

‘Theravada’ means ‘the way of the Elders’, which has been the constant ethos of this tradition right from the beginning. Their basic attitude could be described as: ‘This is the path, which the Buddha had laid down. And so that is the path we are going to follow.’

Already during its origins – and especially as the main religion in Sri Lanka – Theravada Buddhism was maintained as well as renewed during the years, so that it could expand eventually in South-East Asia and later on from there to the West. Whilst Buddhism became established in these geographical regions, the respect and veneration for its original teachings was preserved. This also included an appreciation of the lifestyle, how it was embodied by the Buddha and his original Sangha, i.e. the ordained monastics of the early period.

Of course there was rise and decline during the course of the development of this tradition. It evolved, became wealthy, then corrupt, and finally collapsed under its own weight. After a decline a splinter group very often appeared and returned to the forests, in order to return to the old standards: observing the monastic rules, the practice of meditation and the study of the original teachings. This was a pattern, which was applied again and again over the centuries.

In more recent times – around the middle of the 19th century – the orthodox understanding of the scholars in Thailand was, that in this age it was neither possible to realize full awakening (nibbana) nor to reach profound meditative states (jhana). The revivers of the forest tradition could not accept this statement, which was another reason why they were considered troublemakers and eccentrics by the Sangha hierachy of the time. Therefore many of them took a clear distance from the majority of the study monks of their own Theravada school – Ajahn Chah included. They were of the opinion that genuine wisdom cannot be gained through book learning.

Such views might sound presumptuous or arrogant, unless one acknowledges that the interpretations of the scholars led Buddhism into a cul-de-sac. But the ordained people within the Thai Forest Tradition possessed the determination to orient themselves towards lifestyle and personal experience rather than exclusively towards book knowledge. This represented exactly the right starting point, which allowed the spiritual landscape to become ripe for renewal. And it was exactly this fertile ground, from which the revival of the forest tradition evolved.

The Thai Forest Tradition wouldn’t exist today in its special way if it hadn’t been under the influence of a very special master called Ajahn Mun. The Venerable Ajahn Mun was born in Ubon province around 1870. After his acceptance into the Bhikkhu-Sangha (the order of monks) he sought out the help of another very highly regarded monk, called Ajahn Sao, who was one of the very few forest monks at the time, and asked him for personal guidance in regard to Buddhist mind training. Ajahn Mun had recognized, that besides the practice of meditation, it was crucial for his spiritual progress to stick rigorously to the monastic discipline.

Even though from today’s standpoint these two elements (meditation and strict discipline) don’t seem worth mentioning, in those days the monastic discipline in the area was extremely lax and meditation was viewed with a great deal of suspicion. Throughout the course of many years Ajahn Mun explained and demonstrated the usefulness of meditation, and he thus became a prime example for a very high standard of behaviour for the monastic community. Later on he became the most renowned spiritual teacher of his country. Almost all of the most renowned and respected meditation masters of the 20th century in Thailand were either his direct disciples or were at least deeply influenced by him. Ajahn Chah was one of them.

Ajahn Chah

Ajahn Chah

Venerable Ajahn Chah often pointed out to his disciples, that the Buddha was born in a forest, gained awakening in a forest and also died in a forest. Ajahn Chah followed, for almost his entire adult life, a particular style of practice, which is nowadays known as the Thai Forest Tradition. This tradition is committed to the spirit of a lifestyle which the Buddha himself supported, and is oriented towards the same principles that the Buddha encouraged during his lifetime.

Ajahn Chah (Phra Bodhiñāna Thera) was born in a typical farming family in a rural village in the province of Ubon Rachathani, north-east Thailand, on June 17, 1918. He lived the first part of his life as any other youngster in rural Thailand, and – following the custom – took ordination as a novice in the local village monastery for three years where he learned to read and write, in addition to studying some basic Buddhist teachings. After this he returned to the life of a layperson to help his parents, but – feeling an attraction to the monastic life at the age of twenty – he again entered a monastery, this time for higher ordination as a bhikkhu, or Buddhist monk.

He spent the first few years of his bhikkhu life studying some basic Dhamma, discipline (vinaya), Pāli language and scriptures, but the death of his father awakened him to the transience of life. It caused him to think deeply about life’s real purpose, for although he had studied extensively and gained some proficiency in Pāli, he seemed nowhere nearer to a personal understanding of the end of suffering. Feelings of disenchantment set in, and a desire to find the real essence of the Buddha’s teaching arose. Finally in 1946 he abandoned his studies and set off on a mendicant pilgrimage.

He walked some 400 km to central Thailand, sleeping in forests and gathering almsfood in the villages on the way.

He took up residence in a monastery where the monastic discipline was carefully studied and practiced. While there he was told about Venerable Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto, a most highly respected Meditation Master. Keen to meet such an accomplished teacher, Ajahn Chah set off on foot for the north-east in search of him. He began to travel to other monasteries, studying the monastic discipline in detail and spending a short but enlightening period with Venerable Ajahn Mun, the most outstanding Thai forest meditation master of the 20th century. At this time Ajahn Chah was wrestling with a crucial problem. He had studied the teachings on morality, meditation and wisdom, which the texts presented in minute and refined detail, but he could not see how they could actually be put into practice. Ajahn Mun told him, that although the teachings are indeed extensive, at their heart they are very simple. With mindfulness established, and then, if it is seen that everything arises in the heart-mind (citta): right there is the true path of practice. This succinct and direct teaching was a revelation for Ajahn Chah, and transformed his approach to practice. The Way was clear.

For the next seven years Ajahn Chah practiced in the style of an ascetic monk in the austere Forest Tradition, spending his time in forests, caves and cremation grounds, ideal places for developing meditation practice. He wandered through the countryside in quest of quiet and secluded places for developing meditation. He lived in tiger- and cobra-infested jungles, using reflections on death to penetrate the true meaning of life. On one occasion he practiced in a cremation ground, to challenge and eventually overcome his fear of death. As he sat there, cold and drenched in a rainstorm, he faced the utter desolation and loneliness of a homeless monk.

After many years of travel and practice, he was invited to settle in a thick forest grove near the village of his birth. This grove was uninhabited, known as a place of cobras, tigers and ghosts, thus being – as he said – the perfect location for a forest monk. Venerable Ajahn Chah’s impeccable approach to meditation, or Dhamma practice, and his simple, direct style of teaching, with the emphasis on practical application and a balanced attitude, began to attract a large following of monks and lay people. Thus a large monastery formed around Ajahn Chah as more and more monks, nuns and laypeople came to hear his teachings and stay on to practice with him.

Ajahn Chah’s simple yet profound style of teaching has a special appeal to Westerners, and many came to study and practice with him – quite a few for many years. In 1966 the first Westerner came to stay at Wat Nong Pah Pong: Venerable Sumedho. The newly ordained Venerable Sumedho had just spent his first vassa (‘rains’ retreat) practicing intensive meditation at a monastery near the Laotian border. Although his efforts had borne some fruit, Venerable Sumedho realized that he needed a teacher who could train him in all aspects of monastic life. By chance one of Ajahn Chah’s monks, one who happened to speak a little English, visited the monastery where Venerable Sumedho was staying. Upon hearing about Ajahn Chah, he asked to take leave of his preceptor, and went back to Wat Nong Pah Pong with the monk.

Ajahn Chah willingly accepted the new disciple, but insisted that he receive no special allowances for being a Westerner. He would have to eat the same simple almsfood and practice in the same way as any other monk at Wat Nong Pah Pong. The training there was quite harsh and forbidding. Ajahn Chah often pushed his monks to their limits, to test their powers of endurance so that they would develop patience and resolution. He sometimes initiated long and seemingly pointless work projects, in order to frustrate their attachment to tranquility. The emphasis was always on surrender to the way things are, and great stress was placed upon strict observance of the vinaya.

From that time on, the number of foreign people who came to Ajahn Chah began to steadily increase. By the time Venerable Sumedho was a monk of five ‘rains retreats’ and Ajahn Chah considered him competent enough to teach, some of these new monks had also decided to stay on and train there. In the hot season of 1975, Venerable Sumedho and a handful of Western bhikkhus spent some time living in a forest not far from Wat Nong Pah Pong. The local villagers asked them to stay on and Ajahn Chah consented. Wat Pah Nanachat (‘International Forest Monastery’) came into being, and Venerable Sumedho became the abbot of the first monastery in Thailand to be run by and for English-speaking monks.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho were invited to visit Britain by the English Sangha Trust, a charity with the aim of establishing a locally resident Buddhist Sangha. Seeing the serious interest there, Ajahn Chah left Ajahn Sumedho (with two of his other Western disciples who were then visiting Europe) in London at the Hampstead Vihara. He returned to Britain in 1979, at which time the monks were leaving London to begin Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in Sussex.

During his second visit to Britain, Ajahn Chah once remarked that Buddhism in Thailand resembled an old tree which used to be strong and fertile. But now it was so old, that it would only produce a few fruits, and those were very small with a bitter taste. He compared Buddhism in the West to a young sapling full of youthful energy and potential for growth, but which was in need of adequate care and proper support for its development.

In 1980 Venerable Ajahn Chah began to feel more accutely the symptoms of dizziness and memory lapses which had plagued him for some years. In 1980 and 1981, Ajahn Chah spent the ‘rains retreat’ away from Wat Nong Pah Pong, due to his failing health and the debilitating effects of diabetes. As his illness worsened, he would use his body as a teaching device, a living example of the impermanence of all things. He constantly reminded people to endeavour to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer. This led to an operation in 1981, which however failed to reverse the onset of the paralysis which eventually rendered him completely bedridden and unable to speak. This did not stop the increase of monks and laypeople who came to practise at his monastery, and for whom the teachings of Ajahn Chah were a constant guide and inspiration.

After remaining bedridden and silent for an amazing ten years, carefully tended by his monks and novices, Venerable Ajahn Chah passed away on the 16th of January, 1992, at the age of 74, leaving behind a thriving community of monasteries and lay supporters in Thailand, England, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, France, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the U.S.A (and more recently also in Portugal and Norway), where the practice of the Buddha’s teachings continues under the inspiration of this great teacher.

Although Ajahn Chah passed away in 1992, the training which he established is still carried on at Wat Nong Pah Pong and its branch monasteries, of which there are currently more than three hundred in Thailand. Discipline is strict, enabling one to lead a simple and pure life in a harmoniously regulated community where virtue, meditation and understanding may be skillfully and continuously cultivated. There is usually group meditation twice a day and sometimes a talk by the senior teacher, but the heart of the meditation is the way of life. The monastics do manual work, dye and sew their own robes, make most of their own requisites and keep the monastery buildings and grounds in immaculate shape. They live extremely simply following the ascetic precepts of eating once a day from the almsbowl and limiting their possessions and robes. Scattered throughout the forest are individual huts where monks and nuns live and meditate in solitude, and where they practice walking meditation on cleared paths under the trees.

Wisdom is a way of living and being, and Ajahn Chah endeavoured to preserve the simple monastic lifestyle in order that people may study and practise the Dhamma to the present day. Ajahn Chah’s wonderfully simple style of teaching can be deceptive. It is often only after we have heard something many times that suddenly our minds are ripe and somehow the teaching takes on a much deeper meaning. His skillful means in tailoring his explanations of Dhamma to time and place and to the understanding and sensitivity of his audience was marvelous to see. Sometimes on paper though, it can make him seem inconsistent or even self-contradictory! At such times one should remember that these words are a record of a living experience. Similarly, if the teachings seem to vary at times from tradition, it should be borne in mind that the Venerable Ajahn spoke always from the heart, from the depths of his own meditative experience.